GENIUS Act vs STABLE Act: Will Congress Kill or Fuel Stablecoin Growth?

A full deep-dive into the two competing Stablecoin bills ready to be passed in Congress.

What's going on SQUIDs? Today we’ve got a breakdown of the two Stablecoin bills in the US Congress.

A final stablecoin bill is expected to be passed sometime later in 2025, so its important to understand what’s in the bill and how it’s going to effect our industry going forward.

Introduction

We’re in a bull market. A stablecoin bull market.

Since the bottom of the market post-FTX collapse, the stablecoin supply has doubled in 18 months to $215bn USD, and this isn’t even taking into account the new crypto only entrants like Ondo, Usual, Frax, and Maker.

The stablecoin industry is wildly profitable with current interest rates at 4-5%. Tether booked $14bn(!) worth of profits last year with less than 50 employees. Circle is going to file for IPO in 2025. Everything is stablecoin.

Now that Biden is gone, we’re 100% going to get stablecoin legislation in 2025. Banks have watched as Tether and Circle had a 5 year head start for gaining market traction. Once the new laws are passed legalizing stables, every bank in America will issue their own digital dollar.

Two major legislative proposals are now in play: the Senate’s Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act of 2025 (GENIUS Act) and the House’s Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act of 2025 (STABLE Act).

These bills have been bouncing around forever… but now we’re finally getting consensus and one of them will be passed this year.

Both the GENIUS Act and STABLE Act aim to create federal licensing regimes for “payment stablecoin” issuers, establish strict reserve requirements, and clarify oversight responsibilities.

Payment stablecoins are just a nice term for authorized digital dollars issued against bank or non-bank institution balance sheet. It’s defined as digital assets used for payment or settlement that are pegged to a fixed monetary value (typically 1:1 to the dollar) with reserves held in short term treasuries or cash.

Critics of stablecoins think they will erode government’s ability to control monetary policy. Go read Gorton and Zhang’s epic “Taming Wildcat Stablecoins” for a full breakdown of their fears.

The #1 rule for dollars in the modern age is no depegs.

A dollar is a dollar, no matter where it is.

Deposited into JP Morgan, held in Venmo or PayPal, credits in Roblox. Wherever dollars are used, they must always meet the following two rules:

Every dollar must be interchangeable: There's no mental accounting that labels dollars as "special," "reserved," or tied to a specific purpose. Dollars in JPM can’t be thought of different than what’s held on Tesla’s balance sheet.

Dollars are fungible: All dollars are the “same” no matter where they are, cash, bank deposits, reserves.

The entire fiat financial system is built around this one principle.

This is the Fed’s entire job, ensure the dollar stays pegged and strong. No Depegs.

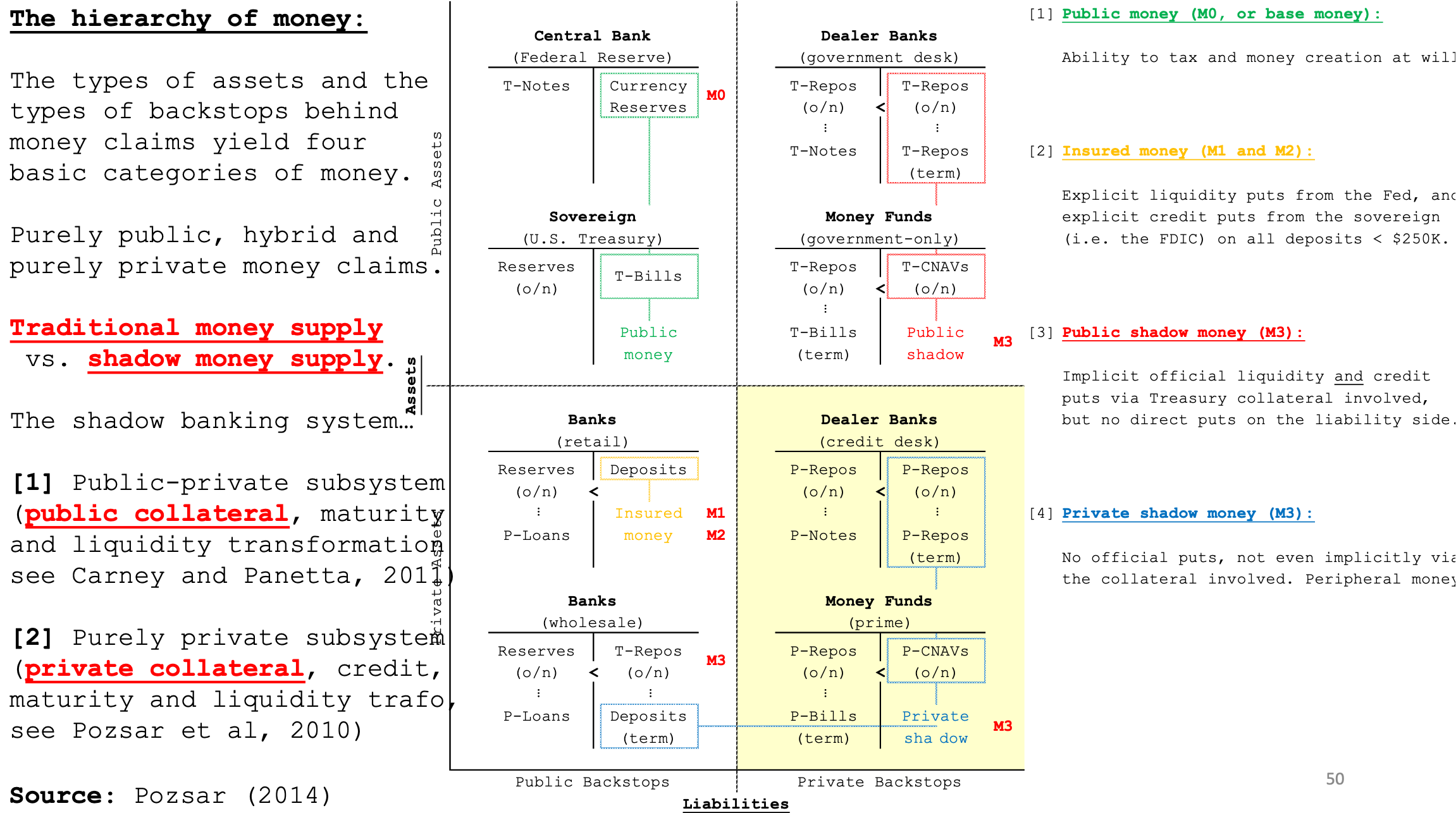

This slide above is from Zoltan Pozsar’s “How the Financial System Works.” It’s the definitive guide to the dollar and will give you loads of context on what these stablecoin bills are trying to achieve.

Right now all stablecoins fit into the lower right box as Private shadow money. If Tether or Circle were shut down or went bust, while apocalyptic for crypto, the impact on the overall financial system would be negligible. Life would go on as we all know it.

Economist fear that by legalizing stablecoins, allowing banks to issue them, and allowing them to be Public shadow money is where the risk lies.

Because the only question that matters in the fiat monetary system is who gets bailouts when shit hits the fan. That’s what the slide above shows.

Remember 2008? US based Mortgage backed securities were a very small part of the global economy, but banks operate on near 100x leverage at all times and collateral is shared around on each other’s balance sheets. So when one bank (Lehmann Bros.) blows up, it started a chain effect of similar implosions due to leverage and balance sheet contagion.

The US Fed, and other monetary institutions like the ECB, had to step in (globally) to ensure that all bank balance sheets would be saved from the spread of the toxic debt. It took billions of bailouts, but the banks were saved. The Fed will always bailout the banks, because without them, the global financial system wouldn’t function, and the dollar might depeg in institutions that have poor balance sheets.

You don't even have to go back to 2008 to see an example of this.

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank collapsed over a single weekend, triggered by a rapid bank run fueled by digital withdrawals and panicked social media chatter. SVB’s failure wasn't caused by risky mortgages, derivatives, or crypto; it was simply due to holding supposedly safe, long-duration US treasury bonds that dramatically lost value as interest rates rose. Yet, despite SVB's relatively small size in the overall banking ecosystem, its collapse threatened systemic contagion, forcing the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury to quickly step in and guarantee all deposits—even those exceeding the standard $250,000 insurance limit. The government's swift intervention underscored the principle: when dollars held anywhere become suspect, the entire financial system can unravel overnight.

The SVB collapse had immediate ripple effects into crypto. Circle, the issuer of USDC—which at the time had about $30 billion in total supply—held a significant portion of its reserves at SVB. Over that weekend, USDC lost its peg by roughly eight cents, briefly trading around $0.92, causing panic across the crypto market. Now, imagine an asset dislocation like this, but on a global scale. That’s precisely what's at stake with the introduction of these new stablecoin bills. By allowing banks to issue their own stablecoins, policymakers risk embedding potentially volatile instruments deeper into the global financial infrastructure, raising the stakes dramatically when—not if—the next financial shock occurs.

The entire point of Zoltan Pozsar's slide above is that when financial disasters strike, it's ultimately the government that has to step in and bail out the financial system.

Today, we have multiple categories of dollars, and each comes with a different level of security.

Dollars issued directly by the government itself—known as M0 dollars—carry the full faith and credit of the United States and are essentially risk-free. However, as we move into the banking system and start categorizing money as M1, M2, and M3, the government's guarantee becomes progressively weaker.

This is precisely why bank bailouts are controversial.

Bank credit lies at the heart of the U.S. financial system, but banks have incentives to pursue maximum risk within the boundaries of the law, often becoming dangerously over-leveraged. When their risk-taking crosses the line, financial crises erupt, and the Fed is compelled to intervene and provide bailouts to prevent total systemic collapse.

The fear is that because the vast majority of money today exists as bank-issued credit—and because banks are deeply interconnected and leveraged—multiple simultaneous bank failures could trigger a domino effect, spreading damage across every sector and asset type.

We witnessed exactly this scenario in 2008.

Few imagined that a seemingly isolated segment of the U.S. housing market could destabilize the global economy, but due to extreme leverage and fragile balance sheets, banks could not withstand the collapse of collateral once deemed safe.

This context helps explain why stablecoin legislation has been so divisive and slow to develop.

Consequently, lawmakers have been cautious, carefully defining exactly what qualifies as a stablecoin and who can issue them.

This caution has produced two competing legislative proposals: the GENIUS Act, which takes a more flexible approach to stablecoin issuance, and the STABLE Act, which imposes strict limitations around eligibility, interest payments, and issuer qualifications.

Both bills, however, represent critical steps forward, potentially unlocking trillions of dollars for on-chain transactions.

Let's examine these two bills in detail to understand how they're similar, how they differ, and what's ultimately at stake.

The GENIUS Act: Senate’s Stablecoin Framework

The GENIUS Act of 2025, formally known as the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act, was introduced in February 2025 by Senator Bill Hagerty (R-TN) along with bipartisan co-sponsors including Senators Tim Scott, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Cynthia Lummis.

On March 13, 2025, it became the first crypto-related bill to clear the Senate Banking Committee (in an 18–6 vote).

Under the GENIUS Act, stablecoins are specifically defined as digital assets that are pegged to a fixed monetary value, typically on a one-to-one basis with the U.S. dollar, and are intended primarily for payments or settlement purposes.

While there are other types of “stablecoins,” like Paxos’ PAXG which is pegged to gold, under the GENIUS Act as currently drafted, tokens pegged to commodities like gold or oil generally wouldn't be covered. In its current form, the bill only applied to fiat currencies.

Commodity-backed tokens typically fall under existing regulations by the CFTC or potentially the SEC, depending on their structure and use, rather than stablecoin-specific legislation.

If and when BTC or gold become the dominant payment currency when we all move to our Bitcoin funded Bastions, then potentially the bill would apply, but for now they’ll remain outside the direct scope of the GENIUS Act.

This is a republican bill. It’s a result of the Biden admin and Dems refusing to draft any crypto focused legislation last administration.

The Act introduces a federal licensing regime mandating that only authorized entities can issue payment stablecoins. The Act establishes three categories of permitted issuers:

Bank subsidiaries – a subsidiary of an insured depository institution (i.e. a bank holding company can have a stablecoin-issuing subsidiary).

Uninsured depository institutions – this could include trust companies or other state-chartered financial institutions that take deposits but aren’t FDIC-insured (often the status of current stablecoin issuers).

Nonbank entities – a new federally chartered category for stablecoin issuers that are not banks (sometimes called “payment stablecoin issuers” in the bill). These would be chartered and supervised by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) at the federal level

As you could guess, all issuers have to maintain full 1:1 backing of their stablecoins with high-quality liquid assets, including cash, bank deposits, or short-term U.S. Treasury instruments. Additionally, these issuers are required to undergo regular public disclosures and audits by registered accounting firms to ensure transparency.

A nice feature of the GENIUS Act is its dual regulatory structure, which allows smaller issuers (those with less than $10 billion in stablecoins outstanding) to remain under state oversight provided that their state's regulatory standards meet or exceed federal guidelines.

Wyoming is the first state exploring issuing its own stablecoin that would be governed by local laws.

Larger issuers are required to operate under direct federal supervision, primarily overseen by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) or the appropriate federal banking regulator.

Importantly, the GENIUS Act explicitly classifies compliant stablecoins as neither securities nor commodities, thus clarifying regulatory jurisdiction and alleviating concerns regarding potential oversight by the SEC or CFTC.

Critics had called for stablecoins to be regulated as securities in the past, and gaining this label means they can be distributed widely and easily.

The STABLE Act: House Rules

Introduced in March 2025 by Representatives Bryan Steil (R-WI) and French Hill (R-AR), the Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act (STABLE Act) is very similar to the GENIUS Act, however, it introduces distinct measures to mitigate financial risks.

Most notably, it explicitly prohibits stablecoin issuers from offering interest or yield to holders, ensuring stablecoins remain strictly as cash-equivalent payment tools rather than investment products.

Additionally, the STABLE Act imposes a two-year moratorium on the issuance of new algorithmic stablecoins—those relying solely on digital assets or algorithms for their peg—pending further regulatory analysis and safeguards.

Two Acts, One Shared Legal Basis

Despite some differences, the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act share significant commonalities, highlighting broad bipartisan consensus on foundational principles for stablecoin regulation. Both bills agree fundamentally on:

Requiring strict licensing of stablecoin issuers to ensure regulatory oversight.

Mandating that stablecoins maintain full 1:1 backing with highly liquid, safe reserve assets to prevent insolvency risks.

Implementing robust transparency requirements, including regular public disclosures and independent audits.

Establishing clear consumer protections, notably asset segregation and priority claims in issuer insolvencies.

Providing regulatory clarity by classifying stablecoins explicitly as neither securities nor commodities, thus streamlining jurisdiction and oversight.

While sharing foundational principles, the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act diverge on three main points

Interest payments: The GENIUS Act allows for the possibility of stablecoins offering interest or yield to their holders, thus opening doors for innovation and broader use cases in the financial sector. In contrast, the STABLE Act strictly prohibits interest payments, firmly limiting stablecoins to being pure payment instruments and explicitly excluding them from functioning as investment or yield-bearing assets.

Algorithmic stablecoins: The GENIUS Act adopts a cautious yet permissive stance, instructing regulators to closely study and monitor such stablecoins without immediately banning them outright. Conversely, the STABLE Act imposes an immediate and clear two-year moratorium on issuing new algorithmic stablecoins, reflecting heightened caution following previous market collapses.

State vs Federal oversight threshold: The GENIUS Act explicitly sets a $10 billion threshold at which issuers must transition from state to federal regulation, clearly defining when a stablecoin issuer becomes systemically significant. The STABLE Act implicitly supports a similar threshold but does not explicitly state the numerical trigger, allowing for regulatory discretion and ongoing adjustment based on market developments.

Why No Interest? The Ban on Stablecoin Yield

A striking element in the House’s STABLE Act (and in earlier proposals) is the prohibition on stablecoin issuers paying interest or any form of yield to coin holders.

In effect, this means a compliant payment stablecoin must function like digital cash or a stored-value instrument – you hold 1 stablecoin, it’s always redeemable for $1, but it will not earn you anything over time.

This contrasts with other financial products like bank deposits, which may earn interest, or money market funds, which accrue yield.

Why impose such a restriction?

There are several legal and regulatory reasons behind the “no-interest rule,” grounded in U.S. securities laws, banking laws, and regulatory guidance.

Avoiding Classification as a Security (Howey Test)

One major reason to forbid interest is to prevent stablecoins from being deemed investment securities under the Howey test.

The Howey test (from a 1946 Supreme Court case) says an asset is an “investment contract” (and thus a security) if there is an investment of money in a common enterprise with an expectation of profits to be derived from the efforts of others. A stablecoin that strictly functions as a payments token is not meant to provide “profit” – it’s just a steady $1 token.

However, the moment an issuer starts offering a return (say a stablecoin that pays 4% APY from the reserves), users are now expecting profits from the issuer’s efforts (the issuer presumably invests the reserves in order to generate that yield). This could trigger the Howey test and invite the SEC to claim the stablecoin is a security offering.

In fact, former SEC Chair Gary Gensler has hinted that some stablecoins could be securities, especially if they mirror shares of a money market fund or have profit characteristics. To sidestep this, the STABLE Act drafters explicitly outlaw any interest or dividend to coin holders, ensuring there is no expectation of profit – the stablecoin remains a utilitarian payment tool, not an investment contract. By doing so, Congress can confidently classify regulated stablecoins as not securities, as both bills state.

The issue with this ban though is that we already have interest bearing stables onchain through Sky’s sUSDS or Frax’s sfrxUSD. Banning interest would just add unecessary roadblocks to companies wanting to explore different business models and systems for their stablecoins.

Maintaining the Banking vs. Non-Banking Divide (Banking Acts)

U.S. banking law traditionally draws a line around deposit-taking as an activity reserved for banks (and thrifts/credit unions). (Deposits are securities)

The Bank Holding Company Act (BHCA) of 1956 and related statutes prevent commercial companies from taking deposits from the public – if you take deposits, you generally need to be a regulated bank or you risk being deemed a bank which triggers a host of regulations.

An instrument where a customer gives you dollars and you promise to return those dollars with interest is essentially a deposit or an investment note.

Regulators have signaled that stablecoins which function too much like bank deposits could implicate these laws.

By banning interest, the STABLE Act authors aim to ensure stablecoins don’t look like uninsured bank accounts in disguise. Instead, they become more akin to stored value cards or prepaid balances, which non-banks are allowed to issue under certain regulations.

In the words of one legal scholar, firms shouldn’t be able to “avoid compliance with the [Federal Deposit Insurance Act] and the [Bank Holding Company Act] simply because their deposit-taking is dressed up as a stablecoin”.

In practice, if stablecoin issuers were allowed to pay interest, they might be competing with banks for deposit-like funds (but without the same regulatory safeguards like FDIC insurance or Fed oversight), which bank regulators would likely find unacceptable.

And remember, the US dollar and financial system is completely dependent and its valued derived from the ability of banks to issue loans, mortgages, and other debt for homes, business, and other goods & trade with massively high leverage, backstopped with retail bank deposits to shore up their reserve requirements.

JP Koning makes an interesting point about PayPal's dollars that's relevant here. Right now, PayPal actually offers two distinct forms of the U.S. dollar.

One type is the regular PayPal balance you're used to seeing—these are dollars stored in a traditional, centralized database. The other type is a newer, crypto-based dollar known as PayPal USD, which lives on a blockchain.

You’d probably assume the traditional version is safer, but surprisingly, it turns out that PayPal’s crypto-based dollars are actually safer and offer stronger consumer protections.

Here’s why: PayPal’s regular dollars aren't necessarily backed by the safest assets.

If you dig through their disclosures, you'll find that PayPal holds only about 30% of customer balances in top-tier assets like cash or U.S. Treasury bills. The rest—nearly 70%—is invested in riskier, longer-duration assets, like corporate debt and commercial paper.

Even more concerning, these traditional balances aren't actually yours in the strict legal sense.

If PayPal were to collapse, you'd become an unsecured creditor, fighting with everyone else PayPal owes money to, and you'd be lucky to recover your full balance.

By contrast, PayPal USD—the crypto version—must be backed 100% by ultra-safe, short-term assets like cash equivalents and U.S. Treasuries, as mandated by the New York State Department of Financial Services.

Not only is the backing safer, but the crypto balances are explicitly yours: the reserves backing these stablecoins must be legally titled for the benefit of holders, meaning if PayPal went bust, you'd get your money back first, ahead of other creditors.

This distinction matters, especially when you think about broader financial stability. Stablecoins like PayPal USD aren't exposed to the wider banking system’s balance sheet risks, leverage, or collateral issues.

In a financial crisis—exactly when you'd want safety—investors could flee to stablecoins precisely because they aren’t tangled up with banks’ risky lending practices or fractional-reserve instability. Ironically, stablecoins could end up functioning more like safe havens rather than the risky speculative tools many assume them to be.

And that’s REALLY bad for the banking system. In 2025, money moves at the speed of the internet. SVB’s collapse was compounded by rapid digital withdrawals by spooked investors, which exacerbated and eventually led to its terminal decline.

Stablecoins are just better money. And the banks are incredibly afraid.

The compromise in these bills is to let non-bank companies issue dollar tokens only if they don’t cross into the realm of paying interest – thereby not directly infringing on banks’ territory of interest-bearing accounts.

This keeps a bright line: banks take deposits and loan them out (and can pay interest), whereas stablecoin issuers under this act must simply hold reserves and facilitate payments (no lending, no interest).

It’s essentially a modern spin on the concept of “narrow banking”, where the stablecoin issuer functions almost like a 100% reserve institution that isn’t supposed to perform maturity transformation or offer yield.

Historical Parallels (Glass-Steagall and Regulation Q)

Interestingly, the notion that money used for payments should not pay interest has a long history in U.S. regulation.

The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, best known for separating commercial and investment banking, also imposed Regulation Q, which for decades prohibited banks from paying interest on demand deposit accounts (checking accounts). The rationale back then was to prevent unhealthy competition for deposits and to ensure banks remained stable (excessive interest offers in the 1920s led to risk-taking that contributed to bank failures).

While Reg Q’s prohibition was eventually phased out (fully repealed in 2011), the underlying principle was that your liquid transaction balances shouldn’t double as interest-earning investments.

Stablecoins, by design, are meant to be highly liquid transaction balances – the crypto equivalent of a checking account balance or cash in your wallet. By disallowing interest on them, lawmakers are echoing that old philosophy: keep payment instruments safe and simple, and separate them from yield-bearing investment products.

This also avoids creating what might look like an uninsured shadow bank. (See Pozsar above and remember private shadow banks don’t get bailouts)

If stablecoin issuers were offering interest, they’d effectively be acting like banks (taking in funds, investing them in, say, Treasuries or loans to generate interest).

But unlike banks, they wouldn’t have oversight of their lending or investment activities beyond the reserve rules, and users might treat them as just as safe as bank deposits without realizing the risks.

Regulators fear that could lead to a “bank run” risk in a crisis – if people thought a stablecoin was as good as a bank account and it started to wobble, they’d all run to redeem, potentially causing broader market stress.

So, the no-interest rule forces stablecoin issuers to hold reserves but not engage in any lending or risk-taking to chase yield, which greatly reduces the risk of a run (since reserves are always equal to liabilities).

This delineation protects the financial system by preventing a large migration of funds into unregulated, quasi-bank instruments.

Effectiveness, Practicality, and Impact

The immediate outcome of the bill is that it brings stablecoins fully into the regulatory perimeter, and should make them safer and more transparent.

Right now, stablecoin issuers like Circle (USDC) and Paxos (PayPal USD) voluntarily follow rigorous state regulations, notably New York’s trust framework, but no unified federal standard exists.

These new laws would establish uniform national standards, giving consumers a higher level of assurance that each stablecoin dollar is genuinely backed 1:1 with high-quality assets like cash or short-term Treasuries.

That’s a big win: it solidifies trust, making stablecoins safer and more credible, especially after highly public blowups like UST and SVB’s collapse.

Plus, by clarifying that compliant stablecoins aren't securities, the constant threat of unexpected SEC crackdowns dissipates, shifting oversight toward more suitable financial stability regulators.

On the innovation front, these acts are surprisingly progressive.

Unlike earlier strict proposals, such as the original 2020 STABLE draft that mandated bank-only issuance, these newer bills provide pathways for fintech and even big tech companies to issue stablecoins by obtaining a federal charter or partnering with banks.

Imagine companies like Amazon, Walmart, or even Google launching branded stablecoins widely accepted across their vast platforms.

Facebook was way ahead of its time when it tried to launch Libra in 2021. Every company will have its own branded dollar. Maybe even influencers and other private persons…

would you buy ElonBucks? Trumpbucks?

Sign us up.

Yet, these bills aren't without meaningful trade-offs.

No one knows what the outcomes for decentralized stablecoins will be. It’s doubtful they could manage capital reserves, licensing fees, and ongoing audits, as well as other compliance costs. This could inadvertently favor large incumbents like Circle and Paxos while squeezing out smaller or decentralized innovators.

What happens to DAI? They might have to leave the US market if they can’t get a license. Same goes from Ondo, Frax, and Usual. None of them are compliant in their current state. We might be headed for a massive shakeup later this year.

Conclusion

The push for stablecoin legislation in the US shows how far the dialogue has come in just a few years.

What was on the fringe is now at the forefront of a new financial revolution and is now on the verge of getting an official regulatory seal of approval, albeit with strict conditions.

We’ve come so far, and these bills will unleash a wave of new issuance.

The GENIUS Act leans slightly more toward allowing market innovations (like interest or new tech) under oversight, while the STABLE Act takes a more precautionary stance on those fronts.

These differences will have to be reconciled as the legislative process continues. Given the bipartisan support and the Trump administration’s public enthusiasm for getting a bill passed by late 2025, however, one of these bills will become a reality.

What a win for our industry and the dollar.

Like this article? Share with a friend.

Great piece. Hats off